My great-grandparents Grace and Luca, grandmother Minnie, and her siblings had to say a quick, likely tearful goodbye to twelve-year-old Mike and begin their new lives without him. I can’t imagine their devastation and Mike’s disappointment at seeing New York City in the distance and being denied entry. They had all passed the medical exam by the shipping line’s doctors in Naples. They must have known there was a possibility they wouldn’t all be accepted into this country, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t a terrible blow to have it happen to them.

My understanding is that families were only given minutes to decide what to do when a family member was being sent back to the old country. If it had been one of the younger kids, maybe someone would have gone back with them. As it was, I imagine Mike was given instructions to stick with the paizane who said he’d watch out for him, and mind the relative who would take care of him until he could return to the U.S. How many letters were written to him describing life in New York and how many reports about his health did he send them? I’d love to have seen that correspondence.

One day I’ll see if I can find out if Luca or Grace had a likely sibling in Gravina that Mike may have lived with when he arrived back in Italy. Maybe an aunt and uncle with no children who might welcome a kid for company or help. Hopefully, a good soul who gave him the love and support he needed.

“The enigma of arrival”

After Luca, Grace, and the other four kids arrived in Manhattan, I hope a familiar face awaited them. If everyone was working, they would somehow have navigated public transportation amid the teeming streets to the relative’s apartment they listed as their destination. Amid their excitement, their hearts must have been heavy that Mike wasn’t with them.

The teeming streets must have been fascinating and maybe overwhelming. Luca had traveled to other countries in Europe, but Naples may have been the largest place the others had seen. Picture the horse-drawn carriages and trolleys, street vendors calling out their wares. Then, in the neighborhood where they were staying, kids playing stickball, women carrying groceries, men coming home from work, the mingling smells of Russian, Italian, and Irish meals being cooked.

In the apartment of Luca’s relative, they likely slept on the parlor floor. As in Italy, there was no running water and most Americans didn’t have electricity or a phone in 1909. The “backahouse” was for necessities and a tap in the yard yielded water to be carried up in pails for cooking and washing. The only source of heat may have been from the kitchen stove.

City Schools

Immigrating meant the end of Minnie’s formal education. She was 15, didn’t speak English and public high schools were just gaining popularity in New York at the time.

I imagine her siblings attended school. Catholic grammar schools (parochial schools,) may have been tuition-free then. There were also many public elementary schools.

The first public high school for girls in NYC was the Wadleigh School. I hope Lillie was able to go there.

Once in school, the younger kids likely picked up English faster and without an accent. When I taught English to some Somali refugees many years ago, I learned that immigrants who learn a new language before puberty, will not have an accent from their country of origin. After that, they do have an accent. I wonder if that extra fifteen months in Italy meant that Mike spoke English with an accent. If so, it may have made a difference in his opportunities.

Living conditions

I wonder about their conditions at the relative’s apartment. where the family initially stayed. How many kids did he have? Were there even two bedrooms? At the time, many immigrants lived in crowded one or two-bedroom apartments, regardless of the number of children. If there was one bedroom, the parents and girls slept in it. If two, the girls, however many there were, slept in the second bedroom. The boys of the family slept in the parlor on beds that were folded up and stored away during the day. At least that was the Italian tradition.

Once Luca had a job, they rented their own apartment. Moving is always expensive and they had to buy furniture and set up a household. There was much to buy and figure out about this new land. On top of that, I know that Luca and Grace sent money back to Italy for Mike’s upkeep. They may have also sent a little extra for the relative’s time and trouble to have another child in their home. In addition to all of those expenses, they needed to save to send Mike money for his second voyage once his rash was gone.

I don’t know if Grace and Luca ever lived or stayed in a tenement, but one of their kids did as an adult. If you ever have a chance, visit the Tenement Museum in Manhattan. In the tenements, there wasn’t even much airflow. There were only windows in rooms with exterior walls and some apartments had only a couple of exterior walls. It took a while for regulations requiring windows into hallways and skylights in stairwells for light.

Brownstones, where I know many of my relatives lived, were a step up.

Luca had to find work. The story I heard was that he found a job because he had the clothes. That always cracked me up as a kid. It made sense though. In Italy, he wore a top hat and tails to drive the coach for Doctor Calderone and his family. In New York, that was what coachmen who worked for undertakers wore, so that was where he found work.

Italian immigrants had a challenge in addition to learning how to navigate the streets and life in a new country without speaking English. Like immigrants before and after them, they faced discrimination. What was unusual, was that they faced it both from within their communities and without. They were treated badly by earlier Italians who had immigrated and their fellow Catholics, the Irish.

Most of the Italian immigrants in the second half of the 19th century were from more prosperous Northern Italy. They were better educated and tended to have more skills. Some had businesses that they came to expand in America. Many of them looked down on the Southern Italians, who they felt embarrassed them and made others think less of Italians in general.

The Irish Catholics had been discriminated against in their own country by what were essentially English protestant overlords. When my people came to the United States, the Irish were the established working-class immigrants. They had built churches. While of the same religion, like many marginalized people, some Irish Americans wanted nothing to do with people even lower than them on the social ladder. Italians were not allowed at their church services but were permitted to have their mass in the church basements. No stained glass windows there I imagine.

Of course, the Italians later looked down upon and discriminated against the next group to arrive- Puerto Ricans, so there’s that.

1910 census details

In the 1910 federal census, Luca, Grace, and the kids were living in an apartment on East 117th Street. Luca is listed as a driver, working for an undertaker. Grace’s occupation was “housewife” and none of the kids had an occupation, including Minnie. Minnie would be married in 1912. The family had only been in the U.S. for five months at the time of the 1910 federal census taken. Luca must have found a job quickly since, according to that document, he hadn’t been unemployed at any time the previous year.

Another detail from that census leapt out at me. For Grace, under the column, “Number of children born”, was the number 6. “Number of living children” 5. I’m glad that we have all of this information, but it must have been upsetting to have to share such a tragedy with a stranger asking questions for the government. She must have lost a baby in Italy. Neighbor women on their page of the census were even more unfortunate, having lost several. Some of their neighbors were fellow Italians, others New Yorkers, or “Russ Polish.”

In January of 1911, Mike rejoined the family and I can imagine the celebration. It may have just been a rash Mike had at Ellis Island. Officials there were concerned with infectious diseases and that poor immigrants anyway, were able-bodied and minded, so they could work. I was told that “Uncle Mike” experienced intermittent poor health as an adult and sometimes couldn’t work, but don’t know the nature of his illness. He was the big family musician and was rumored to be able to play whatever instrument he picked up. The apartment he later shared with Aunt Mary was where my mother and her cousins went to hang out when they played hooky from school. He sounded like fun.

Steinway & Sons

I cannot find Grace, Luca, or any of their kids in the 1915 New York census. I know that by 1911 or 1912 at the latest, Luca was working for a piano company my mother said was Steinway & Sons. There, he worked under a considerably younger man, who was also from the region of Puglia in Italy.

The young man was Patsy. As the story goes, Luca kept inviting Patsy home for Sunday dinner. Patsy kept declining, knowing Luca wanted to introduce him to his eldest daughter. Luca must have worn him down since Patsy finally accepted. He and Minnie married in the fall of 1912.

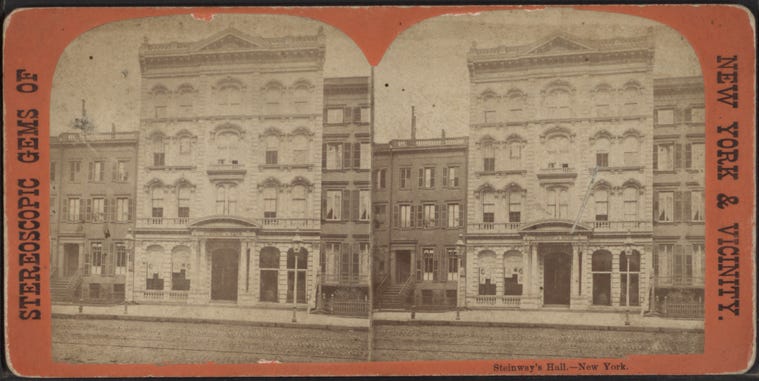

That piano company played an important part in my family’s New York experience for several decades. Steinway was a German company that had factories in Hamburg, Germany, and New York at that time. In New York, Steinway Hall was built on East 14th Street between 1864-1866. I found it remarkable that construction began during the Civil War. The building cost $200,000. It was the second-largest concert hall in New York, and patrons of cultural events had to walk through the piano showroom to the hall. That was a highly successful marketing technique. In 1875, Steinway opened a second concert hall on Wigmore Street in London. That one later moved to St. George and is currently on Marylebone Lane.

In the U.S., the 100,000th grand piano made by Steinway was gifted to the White House. In 1938, the 300,000th grand took the place of the original gift and often resides in the East Room to this day.

I was fascinated to read more about Steinway, and the part the company played in New York’s cultural history and wartime. I had no idea that in addition to their unparalleled grand pianos played by some of the preeminent musicians, they made player pianos. During WWII, Steinway made what were called G.I. pianos. These were light enough to be lifted by four people, and taken on ships or parachuted down to provide music for the troops. The company also built wooden gliders to drop allied troops behind enemy lines.

Piano Mania

I don’t know about Luca, but Patsy and other relatives still worked for piano-making companies at that time. One of my family history surprises was how many family members worked for piano companies in the first half of the twentieth century. Piano manufacturers were thick on the ground in New York City and employed legions of immigrants.

In 1910 New York was the epicenter of the piano industry in the U.S. with 170 factories. Residential streets were full of the sounds of kids taking lessons, too.

Steinway Hall was home to the New York Philharmonic before 1891 when Carnegie Hall opened its doors. The Steinway factory was on 400 acres in then-bucolic Astoria, Queens. I’m not sure that was where Luca or Patsy worked since their job was a final and ongoing stage in the process. They kept those gorgeous musical instruments polished to a shine with a French polish technique described here on Martha Stewart’s show.

Later, Steinway built a village for some of its employees in Astoria. My family never lived there to my knowledge, but I was interested in it since I’d read about other wealthy industrialists doing the same in the U.S. and Europe.

Steinway’s village had well-built brick homes and clean water. Those homes must have been a significant improvement to overcrowded tenements and brownstones in Manhattan. The village had all of the necessities, including green spaces, a school, churches, a post office, and fire station.

Building the village was not entirely altruistic on Steinway’s part. It kept employees away from labor organizers in Manhattan. My guess is that those employees had no excuse to be late to work either. U.S. Steinway is unionized today and many of the employees are still immigrants, mostly from Central and South America now.

Just as Henry Ford controlled or owned every aspect possible of the car manufacturing process, the Steinway factory had its own lumber mill. When Steinway offered public tours not long ago, it was one of the most popular ones in New York City. I wish I’d gone taken one, but they were so popular that it was necessary to book a year or so in advance. I never knew exactly when I’d visit New York that far ahead. Fortunately, you can take an amazing virtual tour. I have a link below.

*****

Resources:

The Statue of Liberty Ellis Island Foundation website has a rich store of photographs, passenger records, and oral histories. Check out the virtual tours or search for an immigrant ancestor. The oral history recordings include the experiences of interpreters, officials, and other employees as well as those of immigrants who were processed there.

You can search for stories of your ancestors or see if the foundation is interested in recording your story about an Ellis Island experience that you’d like to share. I’d forgotten about this and am looking forward to seeing if I can share my stories. A relative on my father’s side had an interesting experience on Ellis Island that I’ll relate at another time.

Here is a link to the virtual Steinway factory tour. I found it fascinating to see how these magnificent grand pianos are made. They use a machine to create the polish my grandfather and great-grandfather used to labor over. The narrator refers to the former process as laborious.

The Tenement Museum is located at 103 Orchard Street and they give moving, informative tours. It looks like they have virtual tours now as well as lesson plans for teachers. This address was chosen since the apartments were abandoned for several decades while ground-floor businesses continued. They were like a sealed time capsule and when someone had the idea for a museum, it was ready-made. They found hundreds of items of canned goods and personal effects and people who lived there donated more. People also recorded oral histories of what their lives had been like in that very building. The histories include what work they did, businesses from their homes, what they cooked, and how they entertained themselves.

Some women worked from home. If I remember right, an organization loaned funds for sewing machines and one story was of a woman tenant who started a successful small dress-making business from her apartment.

Next post-life on Pleasant Avenue.

I agree about empathy and so much else that you wrote. What interesting experiences you've had! You know a lot more about accents than I do. I feel like I'd like to have coffee with you sometime. Maybe we can do that virtually. Thanks so much for reading, Reema. I always enjoy reading your comments.

I really appreciate the level of detail you have shared here and the ways you are trying to imagine what it was like for your immigrant ancestors. I imagine if more people did that, we would have much more empathy about today's immigrants. Your post especially has me think about how classism gets internalized like a chain of each bigger fish eating the next smaller fish. I was further unaware about the sentiments between Northern versus Southern Italians and how the Irish viewed Italian immigrants.

Regarding this quote: "I’m glad that we have all of this information, but it must have been upsetting to have to share such a tragedy with a stranger asking questions for the government." This is something I was thinking about when I used to work with refugees as I noticed most service providers seemed unaware about the impact of having multiple strangers across every point of one's immigration journey asking such intrusive questions especially with the power dynamics involved that can tamper with their consent.

Regarding what you shared here: "I learned that immigrants who learn a new language before puberty, will not have an accent from their country of origin." I think it depends on the communities they are surrounded by both in their upbringing and in the country they moved to. I grew up learning English and Arabic and my accent in both languages is a mix of different accents I heard growing up in an expat dominant city of 200 nationalities on top of having lived in Boston for a decade as an adult.